Author: Wayne McCarthy, Waltham Public Schools and Past Captain Commanding of the Lexington Minute Men

Date: Jan-Feb 1773

Source: Massachusetts Spy, Vol. II, issue 104, suppl, January 29, 1773; Essex Gazette, Vol. V, Issue 136, pp. 1-2 suppl, February 9, 1773

Commentary: Mr. McCarthy speculates, with respect to both political motivations and the mechanics of 18th century printing, on why the Massachusetts Spy and Essex Gazette may have shared a type form printing plate. One surmises that, if they shared anything, it would most likely have been an ‘engraved plate,’ where such a plate is like a single piece of hand-drawn artwork, compared to the text where every letter is individually cast and placed. This instance is so far unique, so we consider here additional aspects suggested by a close inspection of the evidence and what is known about the details of the printing trade. See Part I of Mr. McCarthy’s guest post here as well as the full text of the Massachusetts Spy and Essex Gazette articles under discussion.

“It would seem the easiest thing for the Committees of Correspondence to do in order to blanket as wide an area as possible with consistent information would be to remove as much labor intensive work as possible. Any printers associated with the Committees might have created an engraved copy of their masthead with the word EXTRAORDINARY. Doing so would prevent the user from printing a “regular” edition with the other’s real masthead in it. (While we know of no instance of unauthorized use of a newspaper masthead, Massachusetts cotemporary Nathaniel Ames was plagued by unauthorized printings of his almanac.) Cooperating printers would supply the extraordinary masthead to a single repository capable of printing large quantities and distributing them. It is possible there may have been more than one repository depending on the distances between printing houses. Dispatches would then be required to bring information specific to each local printer to the repository for inclusion in an edition scheduled for distribution in the remote location. For example, the copy for the ads could have been carried to the repository, set in the lock-up, printed with the extraordinary masthead, and then delivered back to the remote location by the same courier. The time involved in production, including setting up the type, proof reading, correcting, setting up the full page, and then printing a run of hundreds of copies would have been quite long. If printed on both sides of the page, I can only imagine how much physical space was required to hang each sheet to dry before being able to print the second side.

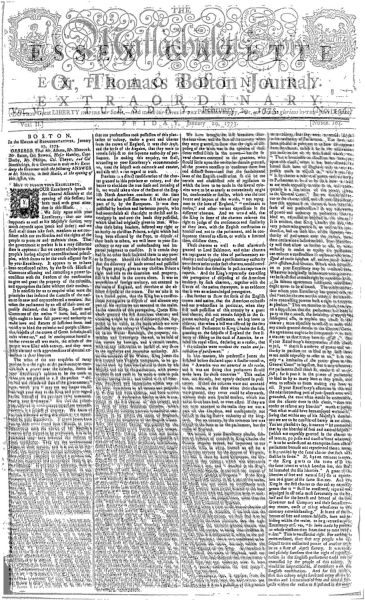

Looking carefully at the copy that is beyond the content of the article, the “ads” as I referred to them, there appears a strong hint that both editions were printed by the same printer. Take a close look at the word “Excellency’s” in each of the two newspapers in the paragraph: “The foregoing answer to his Excellency’s speech was presented (yesterday) (last Thursday).” If you look carefully at the second “l” in Excellency’s you can see what appears to me to be identical defects. That would tell me that all they did was rearrange the lines of type to accommodate different “Ad” space without need for resetting more than the words changing the day from yesterday to last Thursday.

Is it possible there are other newspapers for those dates that may have used the same text with perhaps a different masthead? A search for printers friendly to the Committees of Correspondence may turn up other newspapers that did the same thing, with the central printer changing only the mastheads and the ads. And there is no guarantee that the ads are real. They could just consist of false filler material.

I really think it extremely unlikely that such a large amount of text, assembled one letter and space at a time, would be done exactly the same way in more than one location, and then have the complete locked-up chase carted from one print shop to another. It would have been too expensive, too time-consuming, and impractical to do without dislodging type. And the originating printer might well have asked, “And just when do I get my type back?”

It might be a good idea to look at the material printed WITH the article we’re interested in. I brought them both up again, side by side. Once I did that and compared the type it wasn’t really necessary to read beyond the first line before noticing a similarity that indicates to me they were printed with the same type.

I am now as convinced as possible without eyes on the primary source material that both were printed on the same press, possibly by different pressmen (accounting for the difference in ink coverage). Time constraints mentioned above might indicate multiple shifts of pressmen, some better than others.”

See Mr. McCarthy’s personal study image above. In it he superimposed pdf images, from the Newsbank/AAS database of America’s Historic Newspapers before 1876, of the Massachusetts Spy and Essex Gazette issues under discussion.

Follow

Follow