Commentary: In the previous entry, I expounded on Mr. Frederic C “Rick” Detwiller’s assertion that controversial patriot James Swan appears as a key, and heretofore unidentified, figure in John Trumbull’s iconic painting Bunker’s Hill. The shirtless and shoe-less blonde young man in the painting bravely wards off an aggressive bayonet thrust by a menacing British grenadier on the already mortally wounded Joseph Warren. It is the central vignette of the complex and dramatic painting. It is an image seared into the national consciousness, one that has fanned interest in the dramatic conflict for almost two and a half centuries.

Let us outline James Swan’s peripatetic life. Born in 1754 in Fife, Scotland, he emigrated to Boston around 1765. I have not encountered the circumstances of his arrival in Boston. An Ebenezer Swan signed the 1767 non-importation agreement, suggesting that an elder kinsman was already established in Boston and perhaps had helped place the young James as an apprentice in the mercantile establishment of Thaxter & Co. In addition to his apprenticeship in business, James is said to have joined the St. Andrews Lodge of Masons and also became an active Son of Liberty. In Prof. David Hackett Fisher’s oft-quoted Appendix IV to his Paul Revere’s Ride, Swan appears as a member of the 1771 North End caucus and, as does Benjamin Carp in Defiance of the Patriots, list him as a December 1773 Tea Party ‘Indian.’

Swan was more than a Whig joiner and follower. Not yet 20 years old, he published a controversial tract advocating the abolition of slavery on moral, religious, and business grounds. It was not simply a fluke. Demand was such that he could publish an updated second edition the following year 1773. Professor Carp asserts that Swan was working in concert with contemporaneous black petitioners to end slavery in Massachusetts. The efforts, though unsuccessful in the late colonial years, helped tee up judicial actions to end chattel slavery in Massachusetts within the decade.

With weeks of the outbreak of hostilities in April 1775, James Swan was clerking and keeping accounts for the Massachusetts Provincial Congress committee on supplies. His role in the private sector mercantile business must have been disrupted from the closure of the Port of Boston and then the Siege of Boston. It is in the capacity of low level Provincial Congress functionary that we have previously shared Swan’s claim for clothing losses and damage to his musket at Bunker Hill.

With respect to the later assertion that he served as an aide to Joseph Warren on the battlefield on June 17, 1775, there is a modicum of support in Winthrop’s recollection identified by J.L. Bell. James Winthrop, in an issue of the 1818 North American Review, as quoted here in Boston1775, recalled meeting James Swan and Joseph Warren on the way to the Charlestown peninsula on the day of the battle. Once there, James Winthrop further recalled in 1818 in the Analectic Magazine, as quoted here:

“When I first got there [i.e. where two artillery field pieces were standing near the rail fence], generals [Joseph] Warren and [Israel] Putnam were standing by the pieces and consulting together. Very few men were at that part of the lines. I went forward to the redoubt, and tarried there a little while. Mr. James Swan and myself were in company. Finding that a column of the enemy were advancing toward our left, and not far from Mystic river, we pointed them out to the people without the redoubt, and proposed that some measure should be taken to man the fence, which, when we passed, we had considered as slightly guarded. We two, in the style of the times, were appointed a committee for that purpose. We went directly to the rail fence, and found a body of men had arrived since we had left it. Possibly three hundred would not be an estimate far from the truth.”

Mr. Bell opines on the veracity of this anecdote: “Winthrop’s description of two young men arming themselves and walking onto and around the field is clear and detailed. He mentions that Warren knew them both, which fits with Swan working as a clerk for the Massachusetts government. But he doesn’t claim any heroics for himself. In fact, Winthrop disclaims a rumor that he and his brother were on an important committee. So that source seems quite reliable; I only wish Winthrop had described more of his own experiences of the battle.”

If we accept this recollection at face value, which J.L. Bell is inclined to do, both Swan and Winthrop were “in the style of the times, appointed a committee…” to carry out communications on the battlefield for Israel Putnam and Joseph Warren. One might construe this as being impromptu aides to those leaders. We have not identified as yet an account of these interactions written by James Swan himself or closer in time to June 1775. There is nothing in the anecdote about either young man being wounded, which some later accounts assert.

Swan survived the battle and went on to assume greater responsibility through appointed posts in the Massachusetts wartime government. In 1776 he married Hepzibah Clarke. They had four children between 1777 and 1783 – Hepzibah, Christiana, Sarah, and James Keadie. He invested in privateer enterprises during the war, one of which was the ill fated ship Bunker Hill.

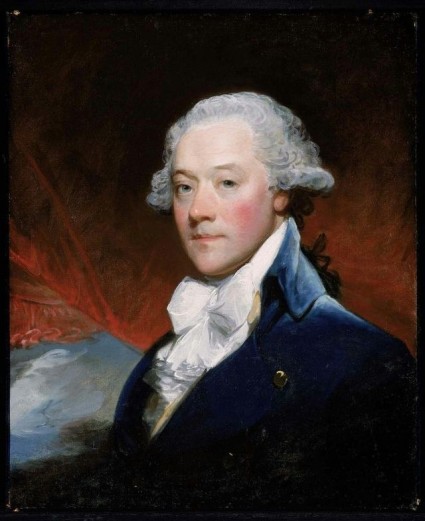

In the Confederation period he lived in high style off of proceeds in finance and real estate. The good times did not continue. Swan departed Massachusetts about 1788 for France. We speculate that the country colleagues of Daniel Shays did not look kindly on the likes of James Swan. Re-established in France, he again did well financially through dealings in United States debt to France. He became a trend setter in style by acquiring furniture and sending it to Massachusetts, where he returned in the late 1790s. The furniture is now at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, where the 1795 portrait of Swan by Gilbert Stuart also resides.

Returning again to France, he ran afoul of the Napoleonic government and ended up in a genteel debtor’s prison for 22 years. That impeccable source, Wikipedia, puts a gloss on Swan’s checkered career. I suspect that there is a whole lot more to it: “…After the American Revolution Swan privately assumed the entire United States French debts at a slightly higher interest rate. Swan then resold these debts at a profit on domestic U.S. markets. The United States no longer owed money to foreign governments, although it continued to owe money to private investors both in the United States and in Europe. This allowed the young United States to place itself on a sound financial footing. On principles of loyalty, he spent 22 years, more than a quarter of his life in a Paris prison.”

As we consider the extent of Swan’s acquaintance, his early abolitionism, financial machinations, influence on architecture and style, and colorful exploits in Europe, I am surprised that no one has yet undertaken a comprehensive biography of him. Perhaps a reader of this website will feel empowered to do so. Fluency in French will be requisite, as many primary sources are likely to reside in France. Swan’s story offers the popular biographical trope of exploring the individual agency of a well connected and controversial individual combined with thematic elements of the formation of the new nation’s financial structure and the introduction of Francophile style. One must resist any tendency to describe his demise, following a prolonged imprisonment for white color crime, as his swan song.

In the next installment, we shall examine closely Trumbull’s methods for designing and executing his historical paintings. Little known sources by Trumbull himself will enable us to evaluate further the claim that he contrived for James Swan a key appearance in Bunker’s Hill.

Sources:

Portrait of James Swan by Gilbert Stuart, 1795. Courtesy Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Swan, James. A dissuasion to Great-Britain and the Colonies, from the slave trade to Africa. Shewing the contradiction this trade bears, both to laws divine and provincial; the disadvantages arising from it, and advantages from abolishing it, both to Europe and Africa, particularly to Britain and the plantations. Also shewing how to put this trade to Africa on a just and lawful footing. Boston: E. Russell [1772]

Swan, James. Dissuasion to Great-Britain and the Colonies: From the Slave-trade to Africa. Shewing the Injustice Thereof, &c: Boston: J. Greenleaf 1773

Swan, James. 1786. “National arithmetick: or, Observations on the finances of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts with some hints respecting financiering and future taxation in this state: tending to render the publick contributions more easy to the people.” Printed by Adams and Nourse, in Court-Street 1786

Swan, James. Causes qui se sont opposées aux progrès du commerce. Paris: Impr. de L. Potier de Lille 1790

Swan, James. An Address to the President, Senate and House of Representatives, of the United States, on The means of Creating a National Paper by Loan Offices, which shall replace that of the discredited Banks, and supercede the use of Gold and Silver Coin. (1819)

Fischer, David Hackett. 1994. Paul Revere’s Ride. New York: Oxford University Press.

Carp, Benjamin J. 2010. Defiance of the Patriots – The Boston Tea Party & the Making of America. New Haven: Yale University Press 2010

Follow

Follow